October 25th – Kaaron Warren – ‘Eleanor Atkins is Dead and Her House is Boarded Up’ (2014) – Read it here. Catch up with the challenge here.

Well that was pretty emotionally devastating as well, hot on the heels of yesterday…

This one pushed a lot of my buttons regarding the passing of time, the changing seasons of life, becoming a person you never thought you would become and not even noticing. It’s desperately sad. I really liked it, but it hollowed out my chest. I’m glad the ghosts are happy.

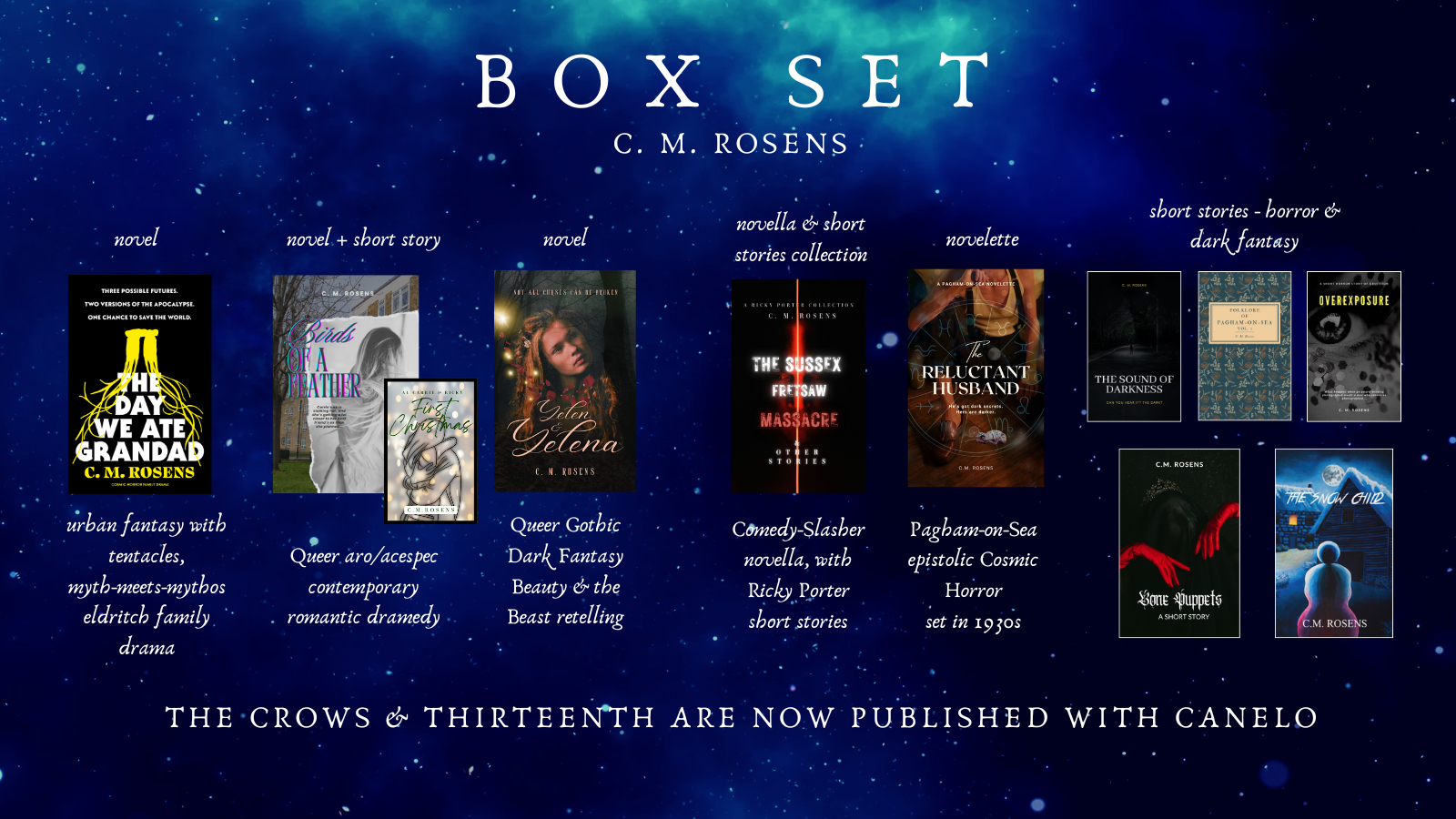

My response to this one is a short reflective piece that might make its way into a book or story at some point.

It’s a Pagham-on-Sea piece again, featuring Eglantine Pritchard and Beverley Wend.

If you haven’t read any of the books, Beverley Wend is the matriarch of a family of eldritch abominations, while Eglantine Pritchard is the one who kept stopping their early ambitions to open a portal for their progenitor to come fully into our world and destroy it.

In this piece, Beverley and Eglantine are at the end of their decades-long drama, a lot of people are dead, and equilibrium has been reached. Ko-Fi members can read Eglantine’s story in the monthly posts and eBooks available to download.

They sat beside one another while not really sitting beside one another, two elderly women on a bench overlooking the promenade, one at each end. They were each dressed for the weather, but neither dressed the same; Beverley had on a blouse and high-waisted, ankle-length skirt with a dark red woollen shawl about her shoulders, fresh from the hairdresser. Eglantine had her usual tweed ensemble, bottle-green skirt covered in terrier hairs. She never bothered with the hairdresser. Her hair was as thick and long as it had been on the day she moved to town, in 1923, coiled at the back of her head in a bun.

Beverley didn’t say anything. Neither did Eglantine. Seagulls called and hovered over the pier, which was closing down. The sandwich kiosk was closed. The ice cream van was looking dismal, but still optimistically open.

A few girls in mini-skirts and boots up to their knees came by arm-in-arm, quite obviously bra-less in the autumn chill under their knitted tops, hair so stiff with sugar and spray that even the stiff breeze coming off the Channel couldn’t budge it.

Eglantine and Beverley tsked in unison, then looked in opposite directions, unwilling to share even a moment of mutual displeasure. Still, it was common ground.

“Young people today,” Beverley said at last, by way of an olive branch.

Eglantine sniffed. “We wouldn’t have dreamed of that in my day. Going about with everything showing. She’s bound to catch a chill, and then she’ll be sorry.”

“You can’t tell them,” Beverley said, picking off the stray cat hairs in her lap. “They won’t take to be told, these days.”

There was another long silence, as both women gathered their thoughts, unused to being in each other’s company in public, and at peace.

“I was very sorry to hear about your sister,” Eglantine said at last. “Sisters, I mean. And your – great-nephew, too.”

“Great-grandson.” Beverley corrected, then tightened her jaw, but forced herself to answer. “Can’t be helped,” she said.

“No,” Eglantine agreed after a while. “I suppose it can’t.”

“I didn’t mean for it to happen,” Beverley said suddenly. Her voice cracked. She cleared her throat, and reached into her handbag for a cough sweet. Eglantine already had hers in her hand, and held them out to her.

There was a pause, and then gloved hand touched gloved hand, the fleetest of touches, and Beverley accepted a lozenge from the proffered packet.

“Thank you,” she said gruffly, and partially unwrapped it. She left it in the paper, gleaming sickly yellow in the sunlight, and contemplated it for a while.

Eglantine returned the packet to her own lap, and looked out over the sea front.

“I don’t want to say I told you so,” she said at last, with a tight, prim expression, “But I did tell you.”

Beverley shot her neighbour a smouldering glance of hatred, but the redness in her pupils faded as quickly as it had flared. She couldn’t deny that. This was her fault. Hector had been a wonderful weapon, but she had been so caught up in perfecting him, trying to bring out his potential, that she had lost sight of the fact that at his core he was, and forever would be, a scared and lonely little boy. It had been a weakness she couldn’t strengthen, a stain on his soul she couldn’t scrub out, no matter how vigorously she tried. His mind had gone, in the end. That was her fault, too. And he had taken her sisters, and then torn himself apart, afraid of anything that would hurt Beverley, his tormentor, his matriarch, his world.

Eileen, of course, couldn’t have lived. Beverley knew that. She had always been wild, and age had made her both wild and bitter. Always thwarted, always scheming, always trying to move mountains for her own grand ends. No, it was a good thing that Hector had taken her.

But Olive…

Unthinkingly, Beverley tipped her head and fixed misty eyes on the space between her and Eglantine, where Olive-in-the-middle would have sat. Hector had simply got the wrong end of the stick, there. He thought Olive was a traitor to the family for her clandestine friendship with their tweedy nemesis. He didn’t know that was with Beverley’s grudging blessing, because she couldn’t admit that without the meddling Welsh woman, she couldn’t keep Eileen in line.

Olive’s absence left a hollow in her chest.

“All over now,” Eglantine said, firmly. “I won’t be having reason to meddle anymore.”

“Two curses are quite enough,” Beverley agreed. “I think you’ll find us quite…” she looked for a word, and fixed upon the terrier hairs sticking to Eglantine’s unbrushed thighs, “…neutered.”

But you will die, Miss Pritchard, Beverley thought to herself. You will die, and then we may not be so neutered anymore.

First, Eglantine had cursed away the family’s ambitions of greatness – you will all be no better than you ought to be – and then, she had taken away their shrine. It was the only way, after the things Eileen used it for, and the things Beverley allowed it to be used for. Everything had got out of hand, was all.

Eglantine nodded sharply. “I’m sure the family will all fall into line neatly enough.”

Of this, Beverley was certain. “Oh, I’m sure.”

It was a strange afternoon, the kind where rain was promised but never quite got around to falling, the kind where the air was on the turn with the season but not fully decided which season it wanted to be. Some people were wearing coats to the pebbled beach, others were still in their shirt-sleeves, and some carried umbrellas they didn’t yet require.

Beverley didn’t like it.

She breathed in, catching a waft of vinegar.

“I never thought it would turn out like this,” she said aloud, more to Olive, who wasn’t there. “I thought there would be dancing, and parties, and I’d be daring like the fashionable ladies who had those short skirts, you know. Them as showed your ankles.”

Eglantine did not pass comment, but remained still, back stiff and straight, staring out to sea.

“It wa’n’t even my idea, really.” Beverley shook her head, and laughed as a sudden absurdity came back to her. “Do you know, I used to make people call me ‘Belle’ for short? Belle. I was a one. No, I never imagined this would be how it was. I wanted to be an artist, and marry one of them painter chaps from a good family and live in Paris, and then I wanted to marry a lad from one of the farms over our way, but he died. And then I thought I’d find me a rich gentleman.” She shook her head. “We found a rich gentleman, all right, the three of us, didn’t we? Not what we wanted at all, in the end.”

Eglantine, who had never in her life wanted any kind of man, gentle or otherwise, pursed her lips at this, and did not commiserate.

Beverley might have been peeved at this some ten or twenty years earlier, but now she took it in good part. “I never did go to Paris,” she said.

“I wouldn’t bother,” Eglantine said. “I had no looks on it myself.”

Beverley tutted. “I hardly think it was at its best during the War, dear.”

“The river smells,” Eglantine said bluntly, the wind picking up so that Beverley strained to hear, “And if I wanted to eat wet p-sies in the rain, I can do that just as well in Llandudno.”

Beverley didn’t catch that word, and coloured. “Wet what, I beg your pardon?”

“Pastries.” Eglantine gave her a look, and her double chin quivered.

“Wasn’t it romantic?” Beverley asked, recovering from this misunderstanding, her youthful reminiscences getting the better of her. “Like the pictures?”

Eglantine shrugged, large bosom rising and falling, and threatening the strained buttons with violent eviction from their moorings. “I suppose it depends if you think straight lines are romantic,” she said dismissively. “I never found romance in uniformity, myself.”

“Where did you find it, then?”

Eglantine shook her head. “Not where I expected,” she said after a while, and her voice was husky. “But that’s the way of it, I dare say.” She took a lozenge for herself, unwrapped it, and put it in her mouth.

Beverley crinkled the paper of her own lozenge, and followed suit.

They sat sucking their cough sweets in silence.

“Well,” Beverley said after a while. “I shan’t keep you.”

Eglantine nodded, folding her arms against the intensifying breeze.

Beverley stood and wrapped her shawl closer about her shoulders. “Don’t sit out here too long,” she said. “You’ll catch your death.”

“Then I’ll have to throw it back again, won’t I?” Eglantine quipped, although she didn’t crack a smile.

Neither did Beverley, although she had to concede that was a pretty good one.

Beverley left her rival on the bench, and made her way stiffly back up the steps to the town, and her own little cottage, and the family who adored her, and she had never felt more unmoored and alone.

Eglantine sat on the bench for an hour longer, by herself, knowing Gwendoline would be at home by the time she got back, and was quite content.

Leave a Reply